The 6.7 quake in 1994 revealed crucial information for experts and residents to get ready next time

When the Northridge earthquake struck the San Fernando Valley in the early hours of Jan. 17, 1994, Craig Renetzky and his family were asleep at home in Reseda three miles from the quake’s epicenter. As walls and windows in their condominium shook, his wife jumped out of bed to check on the baby — who remained peacefully asleep throughout the intense quake.

As Renetzky inspected his home after the temblor — finding broken glass and debris scattered across the floor — he realized the massive quake had made his home uninhabitable.

Red Cross volunteer Craig Renetzky, whose condominium in Reseda was nearly destroyed during the 1994 Northridge earthquake. At the Sherman Oaks American Red Cross office on Thursday, Jan. 11, 2024. (Photo by Dean Musgrove, Los Angeles Daily News/SCNG)

“When you wake up and start walking around the house, we saw significant damage,” he recalled. “There was glass all over the place but we had done things that were helpful. We had strapped down a big bookcase, so nothing fell on us.”

Despite severe damage to his home, Renetzky focused on helping others that day. As a volunteer for the Red Cross, he headed to the organization’s Van Nuys office to assist those displaced in the devastating earthquake.

This week marks 30 years since the Northridge Earthquake struck the heavily populated San Fernando Valley. The 6.7 magnitude earthquake killed 72 people, injured 9,000 residents and left behind $25 billion in damage. Initially, 57 deaths were reported, but a year later a study determined that the death toll reached 72, including those who died of heart attacks linked to the quake.

Los Angeles city limit sign on the 5 Freeway, where the 14 Freeway connector collapsed during the Northridge Earthquake. The quake hit at 4:31 a.m. the morning of Jan. 17, 1994, a powerful jolt that flattened buildings, destroyed homes, damaged freeways, ignited fires, and disrupted water and power. The 6.7-magnitude quake killed 57 people, a number that jumped to more than 70 when those who died from heart attacks were counted, injured 8,700, caused $20 billion in damage, and shattered the nerves of millions of Southern California residents. (Photo By Hans Gutnecht, Los Angeles Daily News/SCNG)

The intense shaking lasted about 10 seconds and was felt hundreds of miles away in places like Las Vegas. It split highways, collapsed buildings, and destroyed vital infrastructure facilities.

With its damage estimated in billions of dollars, the quake became known at that time as the costliest disaster in U.S. history. It also revealed crucial information for scientists, government agencies, and residents about how to prepare for another big one.

Today, people’s memories have faded of the quake that struck the region three long decades ago, and many are not preparing for the next one. Yet some experts say that coping with the COVID-19 pandemic has likely educated even the younger generation to deal with a disaster.

“The COVID response helped people get better prepared,” said Steven F. Goldfarb, a fire safety and emergency planning specialist with the University of Southern California Office of Fire Safety and Emergency Planning. “Because if you prepared for — whether it’s a pandemic, or it’s an earthquake — the idea is that you have the extra food, water, and other supplies.”

“People now understand that when they go to the supermarket,” he said, “those things aren’t going to be there necessarily when they need them.”

People wait outside the Hughes Market in Valencia for a chance to buy water and food after the Northridge Earthquake in January 1994. At many stores the wait in line lasted for hours. (Photo by David Crane, Los Angeles Daily News/SCNG)

One of the lessons Goldfarb learned during the Northridge temblor was the importance of self-resilience.

The Northridge quake shaking began at 4:31 a.m. when most people were at home and sound asleep. But if such shaking had struck in the afternoon, he said, the situation would be very different — families could find themselves stuck at work or school, in places sprinkled across a vast and damaged urban landscape.

“People need to have a family plan on how we communicate with each other during a disaster, especially if we’re separated from each other,” Goldfarb explained.

Theresa Wright tries to make order out of the chaos in the kitchen of her Granada Hills home following the Jan. 17, 1994 Northridge quake. (Photo by Tina Burch, Los Angeles Daily News/SCNG)

Learning other skills from the 1994 quake, like shutting down the utilities at your workplace or home, he added, can save lives the next time.

“In my building, we had a major gas leak and no one knew how to shut the gas off,” Goldfarb recalls. “Those are all things that were really big lessons for being self-resilient, not depending on others, and knowing that you may not be able to get help right away.”

And because of the Northridge quake, many geologists and earth scientists launched deeper studies of Southern California quake faults and ground shaking, said Tim Dawson, program manager of the seismic hazards program at the California Geological Survey.

Before the Northridge quake, Dawson said, “Most of the geologic studies were done on the surface. And so a lot of scientists went back. And they looked at old oil company records and oil well logs, and started identifying faults throughout the L.A. region that were these kinds of blind, or buried, thrust faults that could be potential sources of future earthquakes.”

He said of the Northridge quake, “It was a really interesting event scientifically because it highlighted all these effects that can occur during an earthquake in a very densely urbanized area.”

One of the phenomena scientists have looked into in the aftermath of the Northridge earthquake is the amplification of ground motion, which means that “certain areas tend to amplify the ground motion during the earthquake shaking,” he said.

While the Northridge earthquake’s epicenter was in the northern San Fernando Valley, collapsing a parking structure and severely damaging other buildings at nearby California State Northridge University, it also caused severe damage in faraway Santa Monica, on the other side of the Santa Monica Mountains.

Part of a hillside home overlooking Pacific Coast Highway in Pacific Palisades was lost in a landslide caused by the Northridge Earthquake in January 1994. (Photo by Kim Kulish, Los Angeles Daily News/SCNG)

Scientists later discovered that the intense shaking in the Santa Monica area was caused by local soil structure, which Dawson described as “a lot of sediments that piled up through geologic time, millions of years.”

For decades, geologists and scientists were focused on saving lives, but after the Northridge quake, he said, it became clear that although some of the buildings, especially hospitals, survived the intense shaking, they were still unusable due to structural damage.

“They couldn’t use the (damaged) hospitals after the earthquake, which is a huge problem because there were tens of thousands of people that had injuries,” Dawson said. “They were unable to get immediate hospital care.”

Another destructive impact scientists and planners learned from the Northridge earthquake was the landslides triggered by violent ground shaking. Scientists registered nearly 11,000 landslides throughout the Santa Susana Mountains and other areas north of the San Fernando Valley, he said.

“The landslides were moving. The soils were dry and there were clouds of dust,” Dawson said, and following the quake there was an epidemic of Valley fever, triggered by a fungus that lived in the disturbed soil and infected human lungs.

Looking forward, many experts expect the next earthquake in the Los Angeles area to be more intense than the Northridge quake.

The U.S. Geological Survey estimated in 2008 that the next big temblor could cause more than 1,800 deaths, 50,000 injuries, and $200 billion in damage, bringing “severe and long-lasting disruption,” according to the USGS study called the ShakeOut.

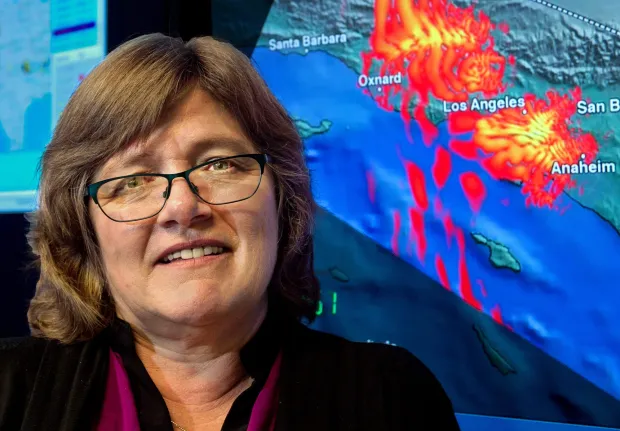

Seismologist Lucy Jones, California’s widely known earthquake expert, oversaw a team of 300 scientists, and engineers, and examined how the potential earthquake would impact the region. The 2008 study examined the consequences of a potential 7.8 earthquake on the southern San Andreas Fault.

Lucy Jones speaking at the USGS at Caltech’s Seismological Laboratory in the Caltech media center Friday, March 18, 2016. (Photo by Walt Mancini/Pasadena Star-News)

Today, Jones says that in the three decades since the Northridge quake, apartment buildings, offices, and hospitals have become safer thanks to an updated state building code, written to save people’s lives.

“The only point of the building code is to prevent life loss,” Jones said in a phone interview. While the main goal of the state’s building code is to keep buildings from collapsing, she said, some structures could be uninhabitable even if they survive a violent shaking — creating a substantial financial loss for homeowners and other building owners.

“We’ve done a very good job about reducing the life risks but not about the financial risks,’ Jones said, noting that people should be aware of the financial loss they might face after a severe earthquake.

Even though the massive Northridge earthquake struck the Valley, it doesn’t mean the big one will hit the same region, said Dawson of the California Geological Survey, because, “Earthquakes globally and regionally are random in space and time.”

The most active faults that can produce larger earthquakes, Dawson said, include the San Jacinto fault which runs through San Bernardino, Riverside, San Diego, and Imperial counties. And of course, the infamous San Andreas fault, which stretches more than 800 miles from the Salton Sea to Cape Mendocino, dividing the state into two parts with San Diego, Los Angeles, and Big Sur on the southern end and San Francisco, Sacramento, and the Sierra Nevada on the northern end.

“Those are the faults that get the most attention because they, in geologic time, move the fastest and have the highest likelihood of producing a future earthquake,” he said.

Still, it doesn’t mean that Los Angeles is safe from being slammed by another large quake, Dawson added. “Because the (Los Angeles) Basin itself is full of faults,” he said. “Those faults have produced earthquakes in the past and they could produce earthquakes in the future.”

Red Cross volunteer Craig Renetzky holds a photograph of a bedroom in his condo in Reseda, nearly destroyed during the 1994 Northridge Earthquake. At the Sherman Oaks American Red Cross office on Thursday, Jan. 11, 2024.

For residents like Craig Renetzky, the Northridge quake was a reminder of how crucial preparedness is.

Experiencing the massive Northridge temblor just “reaffirmed what I already knew, that preparedness was critical. We had earthquake plans in place. We had our contacts. We had emergency supplies and a first aid kit,” Renetzky said.

The family’s preparedness paid off and no one was injured in 1994.

“It’s just a matter of time when we will have another major earthquake in L.A.,” he said. “Now is the time to prepare, not after the fact.”